This article is the 1st in a 2 part series on simplifying and democratizing Double Machine Learning. In the 1st part, we will be covering the fundamentals of Double Machine Learning, along with two basic causal inference applications in python. Then, in pt. 2, we will extend this knowledge to turn our Causal Inference problem into a prediction task, wherein we predict individual level treatment effects to aid in decision making and data-driven targeting.

The conceptual & practical distinctions between statistical/machine learning (ML) and causal inference/econometric (CI) tasks have been established for years— ML seeks to predict, whereas CI seeks to infer a treatment effect or a "causal" relationship between variables. However, it was, and still is, common for the data scientist to draw causal conclusions from parameters of a trained machine learning model, or some other interpretable ML methodology. Despite this, there has been significant strides in industry and across many academic disciplines to push more rigorousness in making causal claims, and this has stimulated a much wider and open discourse on CI. In this stride, we have seen amazing work come out that has begun to bridge the conceptual gap between ML and CI, specifically tools in CI that take advantage of the power of ML methodologies.

The primary motivation for this series is to democratize the usage of & applications of Double Machine Learning (DML), first introduced by Chernozhukov et al. in their pioneering paper "Double Machine Learning for Treatment and Causal Parameters", and to enable the data scientist to utilize DML in their daily causal inference tasks.[1] In doing so, we will first dive into the fundamentals of DML. Specifically, we will cover some of the conceptual/theoretical underpinnings, including the regression framework for causality & the Frisch-Waugh-Lovell Theorem, and then we will use this framework to develop DML. Lastly, we will demonstrate two notable applications of Double Machine Learning:

- Converging towards Exogeneity/CIA/Ignorability in our Treatment given Non-Experimental/Observational Data (particularly when our set of covariates is of high dimensionality), and

- Improving Precision & Statistical Power in Experimental Data (Randomized Controlled Trial’s (RCTs) or A/B Tests)

If this already all feels extremely foreign, I recommend checking out my previous article that covers the regression framework for causality and the Frisch-Waugh-Lovell Theorem. Nevertheless, I will cover these topic below and do my best to simplify and make this accessible to all. Let’s first dive into a quick overview of these theoretical underpinnings!

Regression Framework for Causality & the FWL Theorem

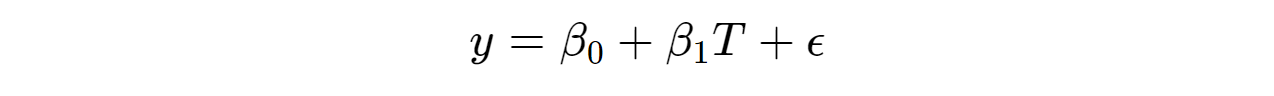

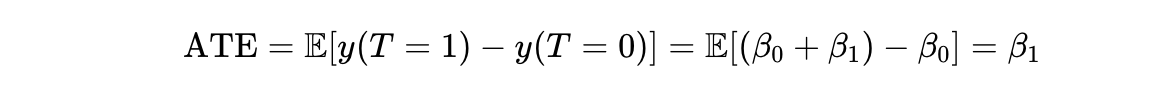

The gold standard for establishing causality is an RCT or A/B test, wherein we randomly assign a subset of individuals to receive treatment, T, (the test group) and others to not receive treatment (the control group), or a different treatment (in "A/B" testing). To estimate the average treatment effect (ATE) of treatment on outcome y, we can estimate the following bivariate linear regression:

Because treatment is randomly assigned, we ensure that treatment is exogenous; that is, independent of the error term, ε, and thus there exists not confounders (a variable that effects both treatment and the outcome) that we have not controlled for— cov(T,ε)=0 (e.g., suppose, as a violation, y = earnings & T = years of education, then we can anticipate a variable such as IQ in ε to confound the true relationship). Because of this independence, the coefficient estimate on T takes on a causal interpretation – the ATE:

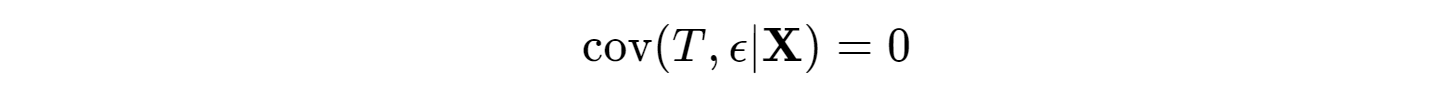

When we are dealing with non-experimental or observational data, it is almost always the case that the treatment of interest is not independent of ε, or endogenous – cov(T,ε)≠0, and there exists confounders that we have not accounted for. In other words, we no longer can parse out the true random variation in our treatment to explain our outcome. In this case, a simple bivariate regression will result in a biased estimate of the ATE (β (true ATE) + bias) due to omitted variable bias. However, if we can control for all possible confounders, X, and the confounding functional form if using parametric models, we can achieve exogeneity in our treatment, or what is also known as the conditional independence assumption (CIA), or Ignorability. In other words again, the remaining variation in our treatment is "as good as random". That is, there are no remaining confounders in the error term, or:

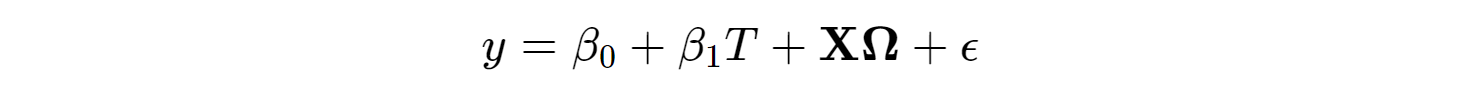

If exogeneity holds (there are no confounders outside of X), then controlling for X in a multiple regression **** allows for the coefficient estimate on T to take on the similar causal interpretation of the ATE:

Warning: It is not best practice to control for every possible covariate, but rather variables that are hypothesized/known to influence both the outcome, y, and treatment of interest, T. This is the concept of a confounder. Conversely, if both y and T influence a variable, we do not want to control for this variable, as this can introduce a spurious association between y and T. This is the concept of a collider variable. We will show an example of this in action further in this article. Additionally, we do not want to include variables that are mediators of our treatment; that is, a covariate that is impacted by the treatment that in turn impacts the outcome. The inclusion of this mediator variable can eat away at the estimate of our treatment effect. In short, we only want to include confounders (and, possibly, non-mediator & non-collider predictors of y to improve precision; this is discussed in example 2 below).

However, in practice, exogeneity/CIA/Ignorability is very difficult to obtain and justify as it is unlikely that we will be able to observe every confounder and control for potential non-linear relationships these confounders may take on. This provides one particular motivation for DML – however, let’s first discuss the FWL theorem, as this allows us to theoretically develop DML.

The FWL theorem is a notable econometric theorem that allows us to obtain the identical ATE parameter estimate, β₁, on the treatment, T, in the multiple regression above (eq. 5) utilizing the following 3 step procedure:

- Separately regress y on X and T on X

- Save the residuals from step 1— call it **y*** and **T***

- Regress **y*** on **T***

In quasi- python code,

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

reg_y = smf.ols(formula='y ~ 1 + X', data = df).fit()

reg_T = smf.ols(formula='T ~ 1 + X', data = df).fit()

y_residual = reg_y.resid

T_residual = reg_T.resid

ATE_model = smf.ols(formula='y_residual ~ 1 + T_residual', data = df).fit()Intuitively, the FWL theorem partials out the variation in T and y that is explained by the confounders, X, and then uses the remaining variation to explain the key relationship of interest (ie, how T effects y). More specifically, it exploits a special type of orthogonal projection matrix of X known as an annihilator matrix or residual-maker matrix to residualize T and y. For a hands-on application of the FWL procedure, see my previous post. This theorem is pivotal in understanding DML.

Note that I have (intentionally) glossed over some additional causal inference assumptions, such as Positivity/Common Support & SUTVA/Counterfactual Consistency. In general, the CIA/Ignorability assumption is the most common assumption that needs to be defended. However, it is recommended that the interested reader familiarize themselves with the additional assumptuons. In brief, Positivity ensures we have non-treated households that are similar & comparable to treated households to enable counterfactual estimation & SUTVA ensures there is no spillover/network type effects (treatment of one individual impacts another).

Double Machine Learning… Simplified!

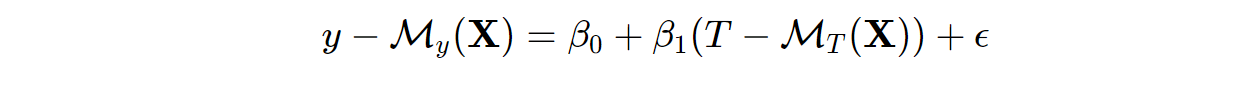

Double Machine Learning, at its core, allows for the residualization/orthogonalization done in steps 1) and 2) of the FWL procedure to be conducted using any highly flexible ML model, thus constructing a partially linear model. That is, we can estimate the ATE via:

where 𝑀𝑦 and MT _ar_e both any ML _models to predict y and T given confounders and/or controls, X, **_ respectively. 𝑀𝑦 and MT _are** also known as the "nuisance functions" as we are constructing functions to partial out the variation in y and T ex_plained by X, which is not of primary interest. To avoid overfitting and to ensure robustness in this approach, we use cross-validation prediction via sample- & cross-fitting. I believe it will be useful again here to see this procedure outlined in quasi- python code:

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_predict

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

M_y = *some ML model*

M_T = *some ML model*

y_residual = df[y] - cross_val_predict(M_y, df[X], df[y], cv=3)

T_residual = df[T] - cross_val_predict(M_T, df[X], df[T], cv=3)

ATE_model = smf.ols(formula='y_residual ~ 1 + T_residual', data = df).fit()Where the coefficient on _Tresidual will be our estimated ATE, with asymptotically normal inference around our estimate. And, that’s it!

This is the procedure behind DML for estimating the ATE. It enables our modeling of the confounding to be highly flexible and non-parametric, particularly in the presence of a high dimensional set of covariates.

I will not dive too deep into the technicalities of why this works, and I will refer the interested reader to the original paper and EconML documentation. However, in brief, DML satisfies a condition known as Neyman Orthogonality (ie, small perturbations in the nuisance functions around the true value has second order effects on the moment condition and thus does not impact our key parameter estimate), which solves for regularization bias, and when combined with the cross-validation procedure in DML, which solves for overfitting bias, we ensure robustness in this method.

There are some very cool extensions on DML that will be covered in part 2 of the series, but for now let’s see this in action via two applications.

DML Applications

Application 1: Converging towards Exogeneity/CIA/Ignorability in our Treatment given Non-Experimental/Observational Data

Recall that we discussed how in the absence of randomized experimental data we must control for all potential confounders to ensure we obtain exogeneity in our treatment of interest. In other words, when we control for all potential confounders, our treatment is "as good as randomly assigned". There are two primary problems that still persist here:

- It is difficult, and impossible in some cases, to truly know all of the confounders and, furthermore, to obtain the data for all these confounders. Solutioning this involves strong institutional knowledge of the data generating process, careful construction of the causal model (i.e., building a DAG while evaluating potential confounders and avoiding colliders), and/or exploiting quasi-experimental designs.

- If we do take manage to take care of point 1, we still have to specify the correct parametric form of confounding, including interactions and higher-order terms, when utilizing a parametric model (such as in the regression framework). Simply including linear terms in a regression may not sufficiently control for the confounding. This is where DML steps in; it can flexibly partial out the confounding in a highly non-parametric fashion. This is particularly beneficial in saving the data scientist the trouble of directly modeling the functional forms of confounding, and allows more attention to be directed towards identifying and measuring the confounders. Let’s see how this works!

Suppose, as a highly stylized example, we work for an e-commerce company and we are tasked with estimating the ATE of an individuals time spent on the website on their purchase amount, or sales, in the past month. However, further assume we only have observational data to work with, but we have measured all potential confounders (those variables that influence both time spent on the website and sales). Let this causal process be outlined via the following Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG):

Let the data generating process be as follows (note that all values & data are chosen and generated arbitrarily for demonstrative purposes, and thus should not necessarily represent a large degree of real world intuition per se outside of our estimates of the ATE):

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# Sample Size

N = 100_000

# Observed Confounders (Age, Number of Social Media Accounts, & Years Member on Website)

age = np.random.randint(low=18,high=75,size=N)

num_social_media_profiles = np.random.choice([0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10], size = N)

yr_membership = np.random.choice([0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10], size = N)

# Additional Covariates (Arbitrary Z)

Z = np.random.normal(loc=50, scale = 25, size = N)

# Error Terms

ε_1 = np.random.normal(loc=20,scale=5,size=N)

ε_2 = np.random.normal(loc=40,scale=15,size=N)

# Treatment DGP (T = g(X) + ε) - Hrs spent on website in past month

time_on_website = np.maximum(10

- 0.01*age

- 0.001*age**2

+ num_social_media_profiles

- 0.01 * num_social_media_profiles**2

- 0.01*(age * num_social_media_profiles)

+ 0.2 * yr_membership

+ 0.001 * yr_membership**2

- 0.01 * (age * yr_membership)

+ 0.2 * (num_social_media_profiles * yr_membership)

+ 0.01 * (num_social_media_profiles * np.log(age) * age * yr_membership**(1/2))

+ ε_1

,0)

# Outcome DGP (y = f(T,X,Z) + ε) - Sales in past month

sales = np.maximum(25

+ 5 * time_on_website # Simulated ATE = $5

- 0.1*age

- 0.001*age**2

+ 8 * num_social_media_profiles

- 0.1 * num_social_media_profiles**2

- 0.01*(age * num_social_media_profiles)

+ 2 * yr_membership

+ 0.1 * yr_membership**2

- 0.01 * (age * yr_membership)

+ 3 * (num_social_media_profiles * yr_membership)

+ 0.1 * (num_social_media_profiles * np.log(age) * age * yr_membership**(1/2))

+ 0.5 * Z

+ ε_2

,0)

collider = np.random.normal(loc=100, scale=50, size=N) + 2*sales + 7*time_on_website

df = pd.DataFrame(np.array([sales,time_on_website,age,num_social_media_profiles,yr_membership,Z]).T

,columns=["sales","time_on_website","age","num_social_media_profiles","yr_membership","Z"])By construction, our treatment of interest (hours spent on the website in the past month) and our outcome (sales in the past month) have the following confounders: Age, Number of Social Media Accounts, & Years Member of Website, and this confounding is arbitrarily non-linear. Furthermore, we can see that the constructed ground truth for the ATE is $5 (outlined in the DGP for sales in the code above above). That is, on average, for every additional hour the individual spends on the website, they spend an additional $5. Note, we also include a collider variable (a variable that is influenced by both time spent on the website and sales), which will be utilized for demonstration below on how this biases the ATE.

To demonstrate the ability of DML to flexibly partial out the highly non-linear confounding, we will run the 4 following models:

- Naïve OLS of sales (y) on hours spent on the website (T)

- Multiple OLS of sales (y) on hours spent on the website (T) and linear terms of all of the confounders

- OLS utilizing DML residualization procedure outlined in eq. (5)

- OLS utilizing DML residualization procedure, including collider variable

The code of this is as follows:

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingRegressor

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_predict

# 1 - Naive OLS

naive_regression = smf.ols(formula='sales ~ 1 + time_on_website',data=df).fit()

# 2 - Multiple OLS

multiple_regression = smf.ols(formula='sales ~ 1 + time_on_website + age + num_social_media_profiles + yr_membership',data=df).fit()

# 3 - DML Procedure

M_sales = GradientBoostingRegressor()

M_time_on_website = GradientBoostingRegressor()

df['residualized_sales'] = df["sales"] - cross_val_predict(M_sales, df[["age","num_social_media_profiles","yr_membership"]], df['sales'], cv=3)

df['residualized_time_on_website'] = df['time_on_website'] - cross_val_predict(M_time_on_website, df[["age","num_social_media_profiles","yr_membership"]], df['time_on_website'], cv=3)

DML_model = smf.ols(formula='residualized_sales ~ 1 + residualized_time_on_website', data = df).fit()

# 4 - DML Procedure w/ Collider

M_sales = GradientBoostingRegressor()

M_time_on_website = GradientBoostingRegressor()

df['residualized_sales'] = df["sales"] - cross_val_predict(M_sales, df[["age","num_social_media_profiles","yr_membership","collider"]], df['sales'], cv=3)

df['residualized_time_on_website'] = df['time_on_website'] - cross_val_predict(M_time_on_website, df[["age","num_social_media_profiles","yr_membership", "collider"]], df['time_on_website'], cv=3)

DML_model_collider = smf.ols(formula='residualized_sales ~ 1 + residualized_time_on_website', data = df).fit()with the corresponding results (see code in appendix for creating this table):

Recall our simulated source of truth for the ATE is $5. Notice that the only model that is able to capture this value is the DML procedure! We can see that the naïve model has a significant positive bias in the estimate, whereas controlling only for linear terms of the confounders in the multiple regression slightly reduces this bias. Additionally, the DML procedure w/ a collider demonstrates a negative bias; this negative association between sales and our treatment that arises from controlling for the collider can be loosely demonstrated/observed by solving for sales in our collider DGP as such:

collider = 100 + 2*sales + 7*time_on_website

# Note the negative relationship between sales and time_on_website here

sales = (collider - 100 - 7*time_on_website)/2These results demonstrate the unequivocal power of using flexible, non-parametric ML models in the DML procedure for residualizing out the confounding! Pretty satisfying, no? DML removes the necessity for correct parametric specification of the confounding DGP (given all of the confounders are controlled for)!

The careful reader will have noticed that we included arbitrary covariate Z in our data generating process for sales. However, note that Z does not directly influence time spent on the website, thus it does not meet the definition of a confounder and thus has no impact on the results (outside of possibly improving the precision of the estimate – see application 2)

Application 2: Improving Precision & Statistical Power in Experimental Data (Randomized Controlled Trial’s (RCTs) or A/B Tests)

It is a common misconception that if one run’s an experiment with a large enough sample size, one can obtain sufficient statistical power to accurately measure the treatment of interest. However, one commonly overlooked component in determining statistical power in an experiment, and ultimately the precision in the ATE estimate, is the variation in the outcome you are trying measure.

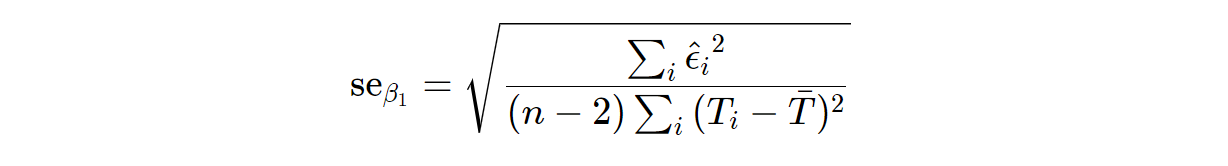

For example, suppose we are interested in measuring the impact of a specific advertisement on an individuals purchase amount, and we anticipate the effect to be small, but non-trivial – say an ATE of $5. However, suppose the standard deviation in individual sales is very large… perhaps, in the $100s or even $1000s. In this case, it may be difficult to accurately capture the ATE given this high variation -that is, we may obtain very low precision (large standard errors) in our estimate. However, capturing this ATE of $5 may be economically significant (if we run the experiment on 100,000 households, this can amount to $500,000). This is where DML can come to the rescue. Before we demonstrate this in action, let’s first visit the formula for the standard error of our ATE estimate from the simple regression in equation (1):

Here we observe that the standard error of our estimate is directly influenced by the size of our residuals (ε). What does this tell us then? If our treatment is randomized, we can include covariates in a multiple OLS or DML procedure, not to obtain exogeneity, but to reduce the variation in our outcome. More specifically, we can include variables that are strong predictors of our outcome to reduce the residuals and, consequently, the standard error of our estimate. Let’s take a look at this in action. First, assume the following DAG (note treatment is randomized so there are no confounders):

Furthermore, suppose the following DGP:

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# Sample Size

N = 100_000

# Observed Confounders (Age, Number of Social Media Accounts, & Years Member on Website)

age = np.random.randint(low=18,high=75,size=N)

num_social_media_profiles = np.random.choice([0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10], size = N)

yr_membership = np.random.choice([0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10], size = N)

# Additional Covariates (Arbitrary Z)

Z = np.random.normal(loc=50, scale = 25, size = N)

# Error Term

ε = np.random.normal(loc=40,scale=15,size=N)

# Randomized Treatment (T) - Advertisement Exposure

advertisement_exposure = np.random.choice([0,1],size=N,p=[.5,.5])

# Outcome (y = f(T,X,Z) + ε) - Sales in past month

sales = np.maximum(500

+ 5 * advertisement_exposure # Ground Truth ATE of $5

- 10*age

- 0.05*age**2

+ 15 * num_social_media_profiles

- 0.01 * num_social_media_profiles**2

- 0.5*(age * num_social_media_profiles)

+ 20 * yr_membership

+ 0.5 * yr_membership**2

- 0.8 * (age * yr_membership)

+ 5 * (num_social_media_profiles * yr_membership)

+ 0.8 * (num_social_media_profiles * np.log(age) * age * yr_membership**(1/2))

+ 15 * Z

+ 2 * Z**2

+ ε

,0)

df = pd.DataFrame(np.array([sales,advertisement_exposure,age,num_social_media_profiles,yr_membership, Z]).T

,columns=["sales","advertisement_exposure","age","num_social_media_profiles","yr_membership","Z"])Here again, we artificially simulate our ground truth ATE of $5. This time, however, we generate sales such that we have a very large variance, thus making it difficult to detect the $5 ATE.

To demonstrate how the inclusion of covariates that are strong predictors of our outcome in the DML procedure greatly improve the precision of our ATE estimates, we will run the following 3 models:

- Naïve OLS of sales (y) on randomized exposure to advertisement (T)

- Multiple OLS of sales (y) on randomized exposure to advertisement (T) and linear terms of all of the sales predictors

- OLS utilizing DML residualization procedure outlined in eq. (5)

The code is as follows:

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingRegressor

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_predict

# 1 - Naive OLS

naive_regression = smf.ols(formula="sales ~ 1 + advertisement_exposure",data=df).fit()

# 2 - Multiple OLS

multiple_regression = smf.ols(formula="sales ~ 1 + advertisement_exposure + age + num_social_media_profiles + yr_membership + Z",data=df).fit()

# 3 - DML Procedure

M_sales = GradientBoostingRegressor()

M_advertisement_exposure = GradientBoostingClassifier() # Note binary treatment

df['residualized_sales'] = df["sales"] - cross_val_predict(M_sales, df[["age","num_social_media_profiles","yr_membership","Z"]], df['sales'], cv=3)

df['residualized_advertisement_exposure'] = df['advertisement_exposure'] - cross_val_predict(M_advertisement_exposure, df[["age","num_social_media_profiles","yr_membership", "Z"]], df['advertisement_exposure'], cv=3, method = 'predict_proba')[:,0]

DML_model = smf.ols(formula='residualized_sales ~ 1 + residualized_advertisement_exposure', data = df).fit()You may notice that we include the ML model to predict advertisement exposure as well. This is primarily for consistency with the DML procedure. However, because we know advertisement exposure is random this is not entirely necessary, but I would recommend verifying the model in our example truly is unable to learn anything (i.e., in our case it should predict ~0.50 probability for all individuals, thus the residuals will maintain the same variation as initial treatment assignment).

With the corresponding results of these models (see code in appendix for creating this table):

First, note that b/c treatment was randomly assigned, there is no true confounding that is occurring above. The poor estimates of the ATE in (1) and (2) are the direct result of imprecise estimates (see the large standard error’s in the parenthesis). Notice how the standard error gets smaller (precision increasing) as we move from (1)-(3), with the DML procedure having the most precise estimate. Draw your attention to the "Residual Std. Error" row outlined in the red box above. We can see how the DML procedure was able to greatly reduce the variation in the ATE model residuals via partialling out the variation that was able to be learnt (non-parametrically) from the predictors in the ML model of our outcome, sales. Again, in this example, we see DML being the only model to obtain the true ATE!

These results demonstrate the benefit of using DML in an experimental setting to increase statistical power and precision of one’s ATE estimate. Specifically, this can be utilized in RCT or A/B testing settings where the variation in the outcome is very large and/or one is struggling with achieving precise estimates and one has access to strong predictors of the outcome of interest.

Conclusion

And there you have it – Double Machine Learning simplified (hopefully)! Thank you for taking the time to read through my article. I hope this article has provided you with a clear and intuitive understanding of the basics of DML and the true power DML holds, along with how you can utilize DML in your daily causal inference tasks.

Stay tuned for part 2 of this series where we will dive into some very cool extensions of DML that turn our causal inference problem into a prediction task, where we go beyond the ATE & predict individual level treatment effects to aid in decision making and data-driven targeting.

As always, I hope you have enjoyed reading this as much as I enjoyed writing it!

Appendix

Creating the pretty tables:

# Example 1

file = open('Example 1.html','w')

order = ['time_on_website','residualized_time_on_website','age','num_social_media_profiles','yr_membership','Intercept']

rename = {'time_on_website':'Treatment: Hours on Website','residualized_time_on_website':'Residualized Treatment: Hours on Website','age':'Age',

'num_social_media_profiles':"# of Social Media Profiles", "yr_membership":"Years of Membership"}

columns = ['Naive OLS','Multiple OLS','DML','DML w/ Collider']

regtable = Stargazer([naive_regression, multiple_regression, DML_model, DML_model_collider])

regtable.covariate_order(order)

regtable.custom_columns(columns,[1,1,1,1])

regtable.rename_covariates(rename)

regtable.show_degrees_of_freedom(False)

regtable.title('Example 1: Obtaining Exogeneity w/ DML')

file.write(regtable.render_html())

file.close()

# Example 2

file = open('Example 2.html','w')

order = ['advertisement_exposure','residualized_advertisement_exposure','age','num_social_media_profiles','yr_membership','Intercept']

rename = {'advertisement_exposure':'Treatment: Exposure to Advertisement','residualized_advertisement_exposure':'Residualized Treatment: Exposure to Advertisement','age':'Age',

'num_social_media_profiles':"# of Social Media Profiles", "yr_membership":"Years of Membership"}

columns = ['Naive OLS','Multiple OLS','DML']

regtable = Stargazer([naive_regression, multiple_regression, DML_model])

regtable.covariate_order(order)

regtable.custom_columns(columns,[1,1,1])

regtable.rename_covariates(rename)

regtable.show_degrees_of_freedom(False)

regtable.title('Example 2: Improving Statistical Power in RCT')

file.write(regtable.render_html())

file.close()Resources

[1] V. Chernozhukov, D. Chetverikov, M. Demirer, E. Duflo, C. Hansen, and a. W. Newey. Double Machine Learning for Treatment and Causal Parameters. ArXiv e-prints, July 2016.

Access all the code via this GitHub Repo: https://github.com/jakepenzak/Blog-Posts

I appreciate you reading my post! My posts on Medium seek to explore real-world and theoretical applications utilizing econometric and statistical/machine learning techniques. Additionally, I seek to provide posts on the theoretical underpinnings of various methodologies via theory and simulations. Most importantly, I write to learn and help others learn! I hope to make complex topics slightly more accessible to all. If you enjoyed this post, please consider following me on Medium!